Galium aparine L.

Family: Rubiaceae

Common names: Bedstraw, Cleavers,

Goosegrass

Tracey Gulledge Plant Monograph Fall Community 2015

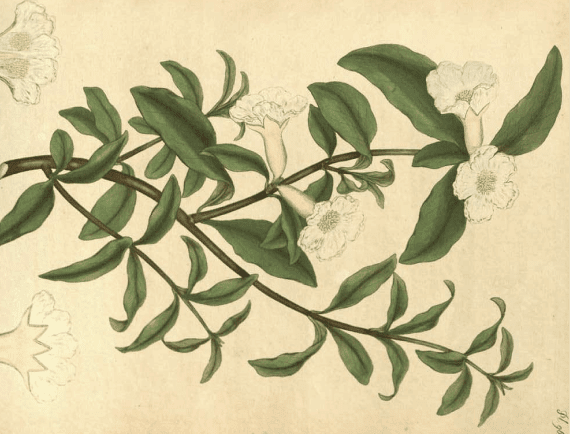

Galium aparine is a common, annual herbaceous species that grows in moist, shady

areas often forming mats in the understory. The oblanceolate leaves form whorls

around a square stem. White, star-shape flowers emerge in spring to early summer.

The flowers are found grouped in twos or threes and form out of the leaf axils. Small,

globular seeds turn brown with age. The plants and seeds are covered in small bristles

which cleave onto passing animals and people. Having spread from its original home in

Asia and Europe, G. aparine is now found across the globe. Considered a noxious

weed by many, cleavers does well in the cooler, winter temperatures but will disappear

in Central Texas with the heat of summer.

Nearly twenty species of cleavers are found throughout Texas with many of them being

found in the moister soils of East Texas or in the Trans-Pecos Mountains found in West

Texas. Local native species include Galium texense, a species found in Texas,

Oklahoma, and Arkansas, and G. proliferum, a species found in Texas and throughout

the Southwest. While other species may exhibit similar medicinal properties, G.aparine

is the preferred wild-crafting species due to its non-native status. Species are normally

identified by the size and number of leaves in a whorl, variations in flower color, and

variations in seeds.

Because of its fondness for disturbed landscapes, care must be taken not to harvest

cleavers from areas that may have potential exposures to pesticides or other harmful

chemicals. Also, cleavers growing on wooded slopes, like those found in the Hill

Country, should probably not be harvested in mass as they may be helping to hold soil

in place. Farmers and gardeners throughout the world consider cleavers to be a weed

due to its ability to take over agriculture fields.

Medicinally, the above ground parts of cleavers are used. Many sources report that

boiling cleavers will destroy the plant’s medicinal properties and prefer the plant fresh or

in a glycerite. When using the fresh plant, care must be taken to deal with the bristles,

which can irritate the throat. Straining is often required to remove the bristles from the

liquid. Juicing is another popular way of using cleavers as is making herbal vinegars.

When cleavers was plentiful this past spring, I enjoyed the juice and found it to be light

and refreshing. I also created my first herbal vinegar using cleavers. Using the fresh

herb in an apple cider vinegar extract, I thought the vinegar was a delicious tonic and

lymph mover. With the addition of some green onions, the cleavers vinegar also made a

wonderful salad dressing base. Externally, I found putting the fresh plant into water

helped reduce my symptoms of eczema, which I have suffered from since I was a child.

Historically, Cleavers was used to strain milk and curdle cheese. Some sources claim

that the more aromatic species were used to stuff mattresses. The roasted seeds have

been used as coffee substitute. In the past, herbalists used cleavers as a diuretic and

for urinary tract issues. In his 1924 book The Working Man’s Model Family Botanic

Guide, William Fox, M.D., reports cleavers to be “a valuable diuretic, useful in many

diseases of the urinary organs, gravel, and dropsy, inflammation of the kidneys and

bladder.” Fox goes on to explain that cleavers can also be used for eczema and other

skin diseases. Maud Grieve wrote in her 1931 book A Modern Herbal that cleavers or

“clivers” as she calls the plant “is extolled for its powers…as a purifier of the blood, the

tops being used as an ingredient in rural spring drinks.” Harvey Wickes Felter states

that the plant was used as a sedative and diuretic in cases of scarlet fever in his 1922

book, The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutic.

Cleavers is considered to be an edible plant. In her book Edible and Useful Plants of

Texas and the Southwest, author and naturalist Delena Tull explains that the young

leaves and stems of cleavers are tender enough to use as a potherb. She recommends

simmering the young leaves and stems in a small amount of water for ten minutes and

then serving with butter and a squeeze of fresh lemon juice. As the plant ages, the

stems become more fibrous and the bristles become stiff, rendering the plant inedible.

Tull also mentions that cleavers, which is in the same botanical family as madder, Rubia

tinctorum, can be used as a fabric dye. Some of the Galium species have roots that will

produce a red dye. As the roots of cleavers tend to be small, harvesting enough to dye

fabric in any real quantity may be a difficult task.

In modern Western herbalism, cleavers is often used as a tonic, as a diuretic and for

skin issues. In his book Making Plant Medicine, Richo Cech, reports using cleavers as

a spring detoxification tonic, which purifies the blood and promotes drainage of the

lymphatic system. Cech also uses the plant for treating urinary issues such as urinary

tract infections, kidney inflammation, and inflammation of the prostate gland. Used

externally, he also uses the plant to treat poison ivy, sunburn and psoriasis.

In a 2015 personal interview with practicing herbalist, Karen Keaton, Karen explained

how she uses cleavers. Karen recommends cleavers often for its diuretic properties

including easing PMS related bloating. She also uses cleavers tincture as an astringent

and lymphatic and liver tonic. In her “younger days”, Karen fondly remembered using

cleavers as a “pre-hangover remedy.” She added that cleavers can also be used as a

refrigerant for the body, which is certainly useful in Central Texas. Finally, Karen

reported that cleavers is safe enough for extended, long-term use. As a gentle

lymphatic mover, cleavers may be of use to pregnant women who are experiencing late

pregnancy edema. During a 2015 interview, Stephanie Berry, Austin midwife and

herbalist, said that she knew of no contraindications of the occasional use of cleavers

with later stage pregnancy. She proposed that a mild cup of cleavers tea might help

gently reduce some of the swelling in an otherwise healthy pregnant woman.

In her new book, Medicinal Plants of Texas, Nicole Telkes, practicing herbalist and

founder and Director of the Wildflower School of Botanical Medicine discusses the use

of cleavers as a burn treatment. She advocates using either the fresh juice of the plant

or freezing the fresh juice into ice cubes which can be used later. If making an extract,

she recommends a fresh 100% glycerite extract with a 1:2 ratio of plant (one part fresh

plant to two parts of 100% glycerin). Nicole advises using cleavers internally to cool

inflammation and to move infection out of the body. She specifically suggests using

cleavers to soothe urinary tract infections.

Reference List

Berry, Stephanie. Personal Interview. May 22, 2015.

Cech, Richo (2000). Making Plant Medicine. Williams, OR: Horizon Herbs, LLC.

Felter, Harvey Wickes (1922), The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and

Therapeutics Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.henriettes-

herb.com/eclectic/felter/galium-apar.html

Fox, William (1924). The Working Man’s Model Family Botanic Guide. Retrieved May

11, 2015, from http://www.swsbm.com/Ephemera/Family_Botanic_Guide-1.pdf

Galium aparine. Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center. University of Texas at Austin,

2015 Retrieved May 12, 2015, from

http://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=GAAP2

Grieve, Maud (1931) A Modern Herbal. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from

http://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/c/cliver74.html

Keaton, Karen. Personal Interview. April 18, 2015.

Telkes, Nicole (2014). Medicinal Plants of Texas. Cedar Creek, Texas: Wildflower

School of Botanical Medicine Publishing.

Tull, Delena (1987). Edible and Useful Plants of Texas and the Southwest. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

United States. Department of Agriculture. PLANTS database. Retrieved May 12, 2015,

from http://plants.usda.gov/java/nameSearch.

Felter, Harvey Wickes (1922), The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and

Therapeutics Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.henriettes-

herb.com/eclectic/felter/galium-apar.html