Passiflora Incarnata (Passifloraceae)

Monograph

Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata) was used traditionally in the

Americas and later in Europe as a calming herb for anxiety, insomnia,

seizures, and hysteria. It is still used today to treat anxiety and

insomnia. Scientists believe passionflower works by increasing levels

of a chemical called gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the brain. GABA

lowers the activity of some brain cells, making you feel more relaxed.

Passionflower is ecologically intriguing, drop-dead gorgeous, and an

incredibly useful herbal medicine and wild edible.

The Latin word for passionflower is Passiflora incarnata. The effects

of passionflower tend to be milder than valerian (Valeriana

officinalis) or kava (Piper methysticum), 2 other herbs used to treat

anxiety. Passionflower is often combined with valerian, lemon balm

(Melissa officinalis), or other calming herbs. Few scientific studies

have tested passionflower as a treatment for anxiety or insomnia,

however, and since passionflower is often combined with other calming

herbs, it is difficult to tell what effects passionflower has on its

own. Passionflower leaves (Passiflora spp.) are the only food source

for gulf fritillary caterpillars (Agraulis vanillae, Nymphalidae) and

butterfly larvae also feed on passionflower leaves.

Passiflora incarnata plant-ant mutualism is so important to certain

species of plants that their survival is contingent on the presence of

their little bodyguards. Some ants even go so far as to girdle the

twigs of neighboring plants that might otherwise outcompete their

plant friend. Passionflower produces extrafloral nectaries at the base

of the leaf, on the very top of the petiole (leaf stalk), and at the

base of the flower, on the little green bracts (leaf-like appendages

below a flower or group of flowers) below the petals (pictured below

is an ant feeding off the extra-floral nectaries on the bracts below

the flower bud). If you spend enough time with the plant you will see

the ants crawling over the plant and pausing periodically to feed at

the nectaries.

Passiflora closests analog is Ashwagandha. One study of 36 people

with generalized anxiety disorder found that passionflower was as

effective as the drug oxazepam (Serax) for treating symptoms. However,

the study lacked a placebo group, so it is not considered to be

definitive. In another study of 91 people with anxiety symptoms,

researchers found that an herbal European product containing

passionflower and other herbal sedatives significantly reduced

symptoms compared to placebo. A more recent study found that patients

who were given passionflower before surgery had less anxiety, but

recovered from anesthesia just as quickly, than those given placebo.

During my studies I performed a weeks proving of passiflora incarnata

and found consistent relief of insomnia and anxiety symptoms.

Botany:

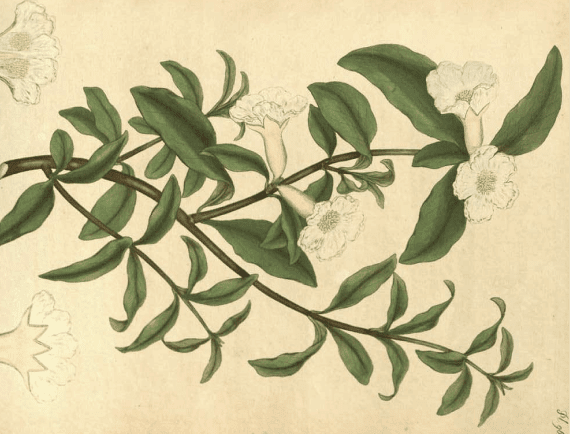

Native to southeastern parts of the Americas, passionflower is now

grown throughout Europe. It is a perennial climbing vine with

herbaceous shoots and a sturdy woody stem that grows to a length of

nearly 10 meters (about 32 feet). Each flower has 5 white petals and 5

sepals that vary in color from magenta to blue. According to folklore,

passionflower got its name because its corona resembles the crown of

thorns worn by Jesus during the crucifixion. Passionflower’s floral

arrangement is so unique that early Christian missionaries decided to

capitalize on its distinctive morphology, and use it as an educational

tool in describing Christ’s crucifixion. The name describes the

passion of Christ and his disciples, although in addition, it does

excite passion in laboratory mice, who have demonstrated increased

mounting of non-estrus females. The passionflower’s ripe fruit is an

egg-shaped berry that may be yellow or purple. Some kinds of

passionfruit are edible.

Above the corona rises the androgynophore (translates to

male-female-bearing), which is the shared female and male reproductive

structure. Rising above the short stalk, there are the five stamens

(male, bearing pollen). Above the stamens rests the pistil, which is

the female part of the flower; the pistil is comprised of three parts:

the ovary, resembling a green ball, giving rise to the three styles

and stigmas (female).

Passionflower has an interesting floral reproductive strategy: on any

given plant, some flowers will be functionally bisexual (with fertile

male and female parts), and some plants will be functionally male

(with both male and female parts present, but only the male is

functioning reproductively).

Parts Used:

The above ground parts (flowers, leaves, and stems) of the

passionflower are used for medicinal purposes.

Available forms include the following:

• Infusions

• Teas

• Liquid extracts

• Tinctures

How to Take It:

Pediatric

No studies have examined the effects of passionflower in children, so

do not give passionflower to a child without a doctor’s supervision.

Adjust the recommended adult dose to account for the child’s weight.

Contra-indications/ Side effects: {x} bradycardia; hypotension;

concurrent use of pharmaceutical sedatives.

According to Mills and Bone[xi], passionflower is in the following

category of herbs:

Drugs that have been taken by only a limited number of pregnancy women

and women of childbearing age, without an increase in the frequency of

malformation of other direct or indirect harmful effects on the human

fetus having been observed. Studies in animals have not shown evidence

of an increased occurrence of fetal damage.

In the American Herbal Products Association Botanical Safety

Book[xii], Passionflower is not contra-indicated in pregnancy or

lactation.

In Herbal Medicines, third edition {vi}, Barnes et al report no

recorded drug/herb interactions, however a hydroalcoholic extract was

reported to potentiate rhythmic rat spasms in isolated rat uterus, and

based on these results, the author’s caution against using

passionflower in pregnancy.

Pregnancy: [viii] [ix] headache and pain, in general; prevention of

herpes outbreak; hypertension; help with insomnia and exhaustion in

postpartum depression; insomnia and anxiety. Please see the notes in

the contra-indications section regarding passionflower’s safety in

pregnancy.

Indications/Usages:[vi] [vii]

Nervous system/antispasmodic: insomnia, anxiety, anxietous depression,

hypersensitivity to pain, headaches, agitation, transitioning from

addictions, tics, hiccoughs, overstimulation, nervine tonic in

preventing outbreaks of the herpes simplex virus, stress-induced

hypertension, and menstrual cramps. The mandala-like flower

demonstrates the powerful signature of its use in circular thinking,

especially during insomnia; passionflower is especially suited for

folks who have a hard time letting things go, mulling them over

incessantly in a repetitive manner.

Children: insomnia; trouble sleeping through the night; teething;

colic; adjunct treatment in asthma; especially with panic around

asthma attacks; whooping cough. See the notes below on calculating

dosages for children.

Determining dosage in children by weight:

To determine the child’s dosage by weight, you can assume that the

adult dosage is for a 150-pound adult. Divide the child’s weight by

150. Take that number and multiply it by the recommended adult dosage.

For example, if your child weighs 50 pounds, she will need one-third

the recommended dose for a 150-pound adult. If the adult dosage is

three droppers full of a tincture, she will need one third of that

dose, which is one dropper full (1/3 of 3 droppers full). A 25-pound

child would need one-sixth the adult dose, so he would receive one

half of a dropper full (1/6 of 3 droppers full).

Adult

The following are examples of forms and doses used for adults. Speak

to your doctor for specific recommendations for your condition:

• Tea: Steep 0.5 – 2 g (about 1 tsp.) of dried herb in 1 cup boiling

water for 10 minutes; strain and cool. For anxiety,

drink 3 – 4 cups per day. For insomnia,

drink one cup an hour before going to bed.

• Fluid extract (1:1 in 25% alcohol): 10 – 20 drops, 3 times a day

• Tincture (1:5 in 45% alcohol): 10 – 45 drops, 3 times a day

Precautions:

The use of herbs is a time honored approach to strengthening the body

and treating disease. Herbs, however, can trigger side effects and can

interact with other herbs, supplements, or medications. For these

reasons, you should take herbs with care, under the supervision of a

health care provider.

Do not take passionflower if you are pregnant or breastfeeding.

For others, passionflower is generally considered to be safe and

nontoxic in recommended doses.

Possible Interactions:

Passionflower may interact with the following medications:

Sedatives (drugs that cause sleepiness) — Because of its calming

effect, passionflower may make the effects of sedative medications

stronger. These medications include:

• Anticonvulsants such as phenytoin (Dilantin)

• Barbiturates

• Benzodiazepines such as alprazolam (Xanax) and diazepam (Valium)

• Drugs for insomnia, such as zolpidem (Ambien), zaleplon (Sonata),

eszopiclone (Lunesta), ramelteon (Rozerem)

• Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline (Elavil),

amoxapine, doxepin (Sinequan), and nortriptyline

(Pamelor)

Antiplatelets and anticoagulants (blood thinners) — Passionflower may

increase the amount of time blood needs to clot, so it could make the

effects of blood thinning medications stronger and increase your risk

of bleeding. Blood thinning drugs include:

• Clopidogrel (Plavix)

• Warfarin (Coumadin)

• Aspirin

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAO inhibitors or MAOIs) — MAO

inhibitors are an older class of antidepressants that are not often

prescribed now. Theoretically, passionflower might increase the

effects of MAO inhibitors, as well as their side effects, which can be

dangerous. These drugs include:

• Isocarboxazid (Marplan)

• Phenelzine (Nardil)

• Tranylcypromine (Parnate)

Alternative Names:

Passiflora incarnata; Maypop

• Reviewed last on: 6/23/2011

• Steven D. Ehrlich, NMD, Solutions Acupuncture, a private practice

specializing in complementary and alternative medicine, Phoenix, AZ.

Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network.

Edible Fruit

Passionflower is also called maypop, the origin of the name is often

attributed to children’s proclivity for jumping on the hollow fruits

for the simple joy of hearing them “pop”. Daniel Austin demystifies

this common etymological misconception in Florida Ethnobotany: “The

names maricock and maracocks gave rise to maracoc, maycock, maypop

(Alabama, North Carolina), mollypop (Alabama, North Carolina) ……All of

these names are supposedly derived from mahcawq (Powhatan), akin to

machkak (Menomini)…”[ii]

The ripe fruits have a spongy partition, interesting in texture, which

bears the ripe whitish yellow edible flesh surrounding the black hard

seeds. I pop open the fruits when they are starting to turn yellow and

begin to wrinkle, and slurp up the seedy flesh. I prefer to chew up

the crunchy edible seeds, but some folks opt to spit them out. The

fruit was eaten and perhaps cultivated by Native Americans as

evidenced by historical accounts and the presence of seeds of in many

archeological sites. One historical account from 1612 stated, “… yt is

a good Sommer Cooling fruict, and in every field where the indigenous

people plant their Corne be Cart-loades of them.” [iii]

It is likely that Native people encouraged this native weedy vine in

their corn/bean/squash patches typical of traditional polyculture

farming methods (growing different species of plants together, and

allowing/encouraging weedy edibles to fill in bare patches).

The taste is sour/sweet, with the unripe fruits being decidedly

sourer. The passion fruit of commerce is the closely related

Passiflora edulis, native to South America, now grown throughout the

tropics for its tasty fresh fruit and juice.

Personal experience from Herbalists:

I use passionflower, primarily in tincture form for insomnia.

Passionflower is one of the herbs I use commonly for dysmenorrhea

(menstrual cramps), often in combination with motherwort, black

cohosh, and kava kava. Many women find relief with passionflower for

cranky PMS moments.

Considered safe for children, it is beneficial internally to take the

edge off teething, and to help children relax when they are climbing

up the walls. Many parents use it to help children who wake frequently

throughout the night sleep more soundly. As one of our safer

anti-anxiety herbs, it can be helpful in treating children’s acute or

chronic anxiety, and also to help them deal with an acutely traumatic

or stressful situation.

Passionflower is one of my favored remedies for acute musculoskeletal

pain; I use it in combination with meadowsweet, black birch, and

skullcap for muscle strains, sprains and joint inflammation in

general.

Actions:

• hypnotic (sleep-aid)

• analgesic (pain-reliever)

• hypotensive (lowers blood pressure)

• nervine

• anxiolytic (anti-anxiety)

• anti-spasmodic

• antidepressant

Energetics: slightly cooling and drying, mildly bitter

Traditional Uses: The Cherokee used the roots as a poultice to draw

out inflammation in thorn wounds; tea of the root in the ear for

earache; and tea of the root to wean infants. [iv] The Houma people

infused the roots as a blood tonic. ii

It is interesting to note that contemporary herbalists use primarily

the leaves, stems and flowers, whereas the ethnobotanical literature

cites medicinal use of the roots only. In discussing its inclusion

into the Eclectic material medica, Felter and Lloyd state in King’s

American Dispensatory:[v]

Passiflora was introduced into medicine in 1839 or 1840 by Dr. L.

Phares, of Mississippi, who, in the New Orleans Medical Journal,

records some trials of the drug made by Dr. W. B. Lindsay, of Bayou

Gros Tete, La. The use of the remedy has been revived within recent

years, Prof. I. J. M. Goss, M. D., of Georgia, having introduced it

into Eclectic practice. Prof. Goss, who introduced it to the Eclectic

profession, employed the root and its preparations. We know of

physicians who prefer the tincture of the leaves, and others still,

who desire the root with a few inches of the stem attached.

Eclectic specific indications and uses: {v} irritation of brain and

nervous system with atony; sleeplessness from overwork, worry, or from

febrile excitement, and in the young and aged; neuralgic pains with

debility; exhaustion from cerebral fullness, or from excitement;

convulsive movements; infantile nervous irritation; nervous headache;

tetanus; hysteria; oppressed breathing; cardiac palpitation from

excitement or shock.

Michael Moorisms:[x] Cardiovascular excess in mesomorphs, sthenic

middle-aged women; complementary with Crataegus, lowers diastolic

pressure; PMS depression, PMS with insomnia; insomnia in sthenic

individuals; and headache in hypertensive states with tinnitus.

Cultivated/Wildcrafted: Passionflower is abundant throughout an

extensive range, so it’s not under threat as a species. Although, in

the peripheries of its range, it may be only sporadically found. At

the time of this writing, most of the major herbal distributors in the

U.S. are selling organically grown herb from Italy, which is

surprising considering its abundance and ease of cultivation in the

southeastern U.S.

Part used: Leaves, stem, and flowers, harvest when the leaves are

green and vital

Preparation & Dosage:

Tincture: 1:2 95% fresh herb

1:5 50 % freshly dried herb

Both preparations: 2-4 droppers full up to three times/day

Tea: .5 to 2 grams of herb per cup of water as an infusion up to 3 times/day

References:

Akhondzadeh S, Naghavi HR, Vazirian M, Shayeganpour A, Rashidi H,

Khani M. Passionflower in the treatment of generalized anxiety: a

pilot double-blind randomized controlled trial with oxazepam. J Clin

Pharm Ther. 2001;26(5):369-373.

Akhondzadeh S. Passionflower in the treatment of opiates withdrawal: a

double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther.

2001;26(5):369-373.

Barbosa PR, Valvassori SS, Bordignon CL Jr, Kappel VD, Martins MR,

Gavioli EC, et al. The aqueous extracts of Passiflora alata and

Passiflora edulis reduce anxiety-related behaviors without affecting

memory process in rats. J Med Food. 2008 Jun;11(2):282-8.

[vi] Barnes, Joanne, et al. Herbal Medicine, Third Edition

Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J. Herbal Medicine: Expanded

Commission E Monographs. Newton, MA: Integrative Medicine

Communications; 2000:293-296.

[i] Dai, C. and Galloway, L. F. (2012), Male flowers are better

fathers than hermaphroditic flowers in andromonoecious Passiflora

incarnata. New Phytologist, 193: 787-796.

Dhawan K, Kumar S, Sharma A. Anxiolytic activity of aerial and

underground parts of Passifloraincarnata. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:922-6.

Dhawan K, Kumar S, Sharma A. Anti-anxiety studies on extracts of

Passiflora incarnata Linneaus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;78:165-70.

Elsas SM, Rossi DJ, Raber J, White G, Seeley CA, Gregory WL, Mohr C,

Pfankuch T, Soumyanath A. Passionflora incarnata L. (Passionflower)

extracts elicit GABA currents in hippocampal neurons in vitro, and

show anxiogenic and anticonvulsant effects in vivo, varying with

extraction method. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(12):940-9.

Ernst E, ed. Passionflower. The Desktop Guide to Complementary and

Alternative Medicine. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2001:140-141.

[v] Felter and Lloyd. King’s American Dispensatory.

Grundmann O, Wang J, McGregor GP, Butterweck V. Anxiolytic Activity of

a Phytochemically Characterized Passiflora incarnata Extract is

Mediated via the GABAergic System. Planta Med. 2008

Dec;74(15):1769-73.

[iv] Hamel, B. and Chiltoskey, Mary U. Cherokee Plants and their uses-

a 400 year history

[vii] Hoffman, David. Medical Herbalism

Lakhan SE, Vieira KF. Nutritional and herbal supplements for anxiety

and anxiety-related disorders: systematic review. Nutr J. 2010;9:42.

Larzelere MM, Wiseman P. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Prim Care.

2002 Jun;29(2):339-60, vii. Review.

[xii] McGuffin, Michael et al. American Herbal Products Association’s

Botanical Safety Handbook

[xi] Mills, S. and Bone, K. The Essential guide to Herbal Safety

Miyasaka L, Atallah A, Soares B. Passiflora for anxiety disorder.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD004518.

[x] Moore, Michael. Southwest School of Botanical Medicine, 2001.

Author’s personal class notes.

Movafegh A, Alizadeh R, Hajimohamadi F, Esfehani F, Nejatfar M.

Preoperative oral Passiflora incarnata reduces anxiety in ambulatory

surgery patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesth

Analg. 2008 Jun;106(6):1728-32.

[viii] Romm, Aviva Jill. The Natural Pregnancy Book – Herbs,

Nutrition, and other Holistic Choices.

[ix] Romm, Aviva et al. Botanical Medicine for Women’s Health

Rotblatt M, Ziment I. Evidence-Based Herbal Medicine. Philadelphia,

PA: Hanley & Belfus, Inc; 2002;294-297.

[iii] Strachney, Wm. (1612) 1953. The Historie of Travell into

Virginia Britania. London (Wright, L. B. and

Freund, V., Eds. Reprinted by Hakluyt Society, London.)